The creativity of author, designer, broadcaster Ben Arogundade

Classic Black Actresses of 1940s Hollywood: Hattie McDaniel Kickstarted Diversity at the Oscars in ‘Gone With The Wind’

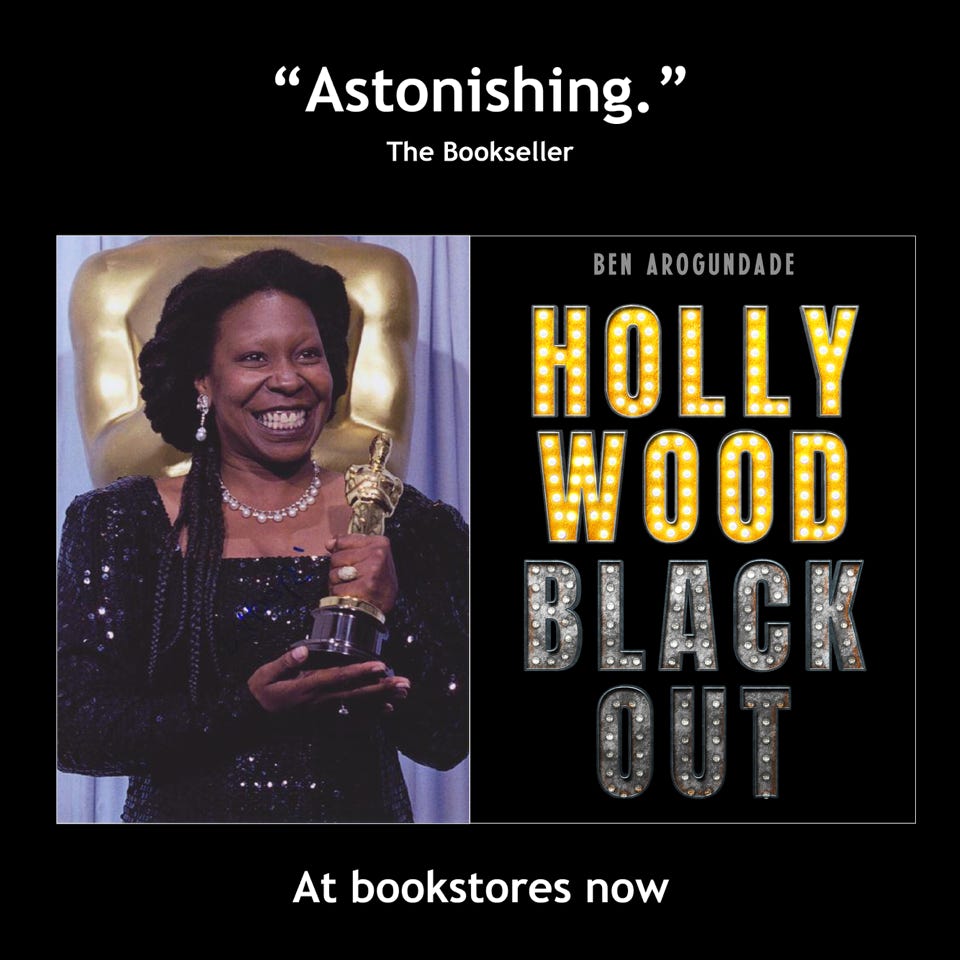

THIS YEAR MARKS THE 85TH anniversary of the beginning of diversity and inclusion at the Academy Awards, when Hattie McDaniel became the first non-white actor to win an Oscar, for Best Supporting Actress in Gone With The Wind. In an excerpt from his new book, HOLLYWOOD BLACKOUT, Ben Arogundade. looks back at her eventful life and career, and her role as a trailblazer of Hollywood’s Golden Age. Feb.28.2025.

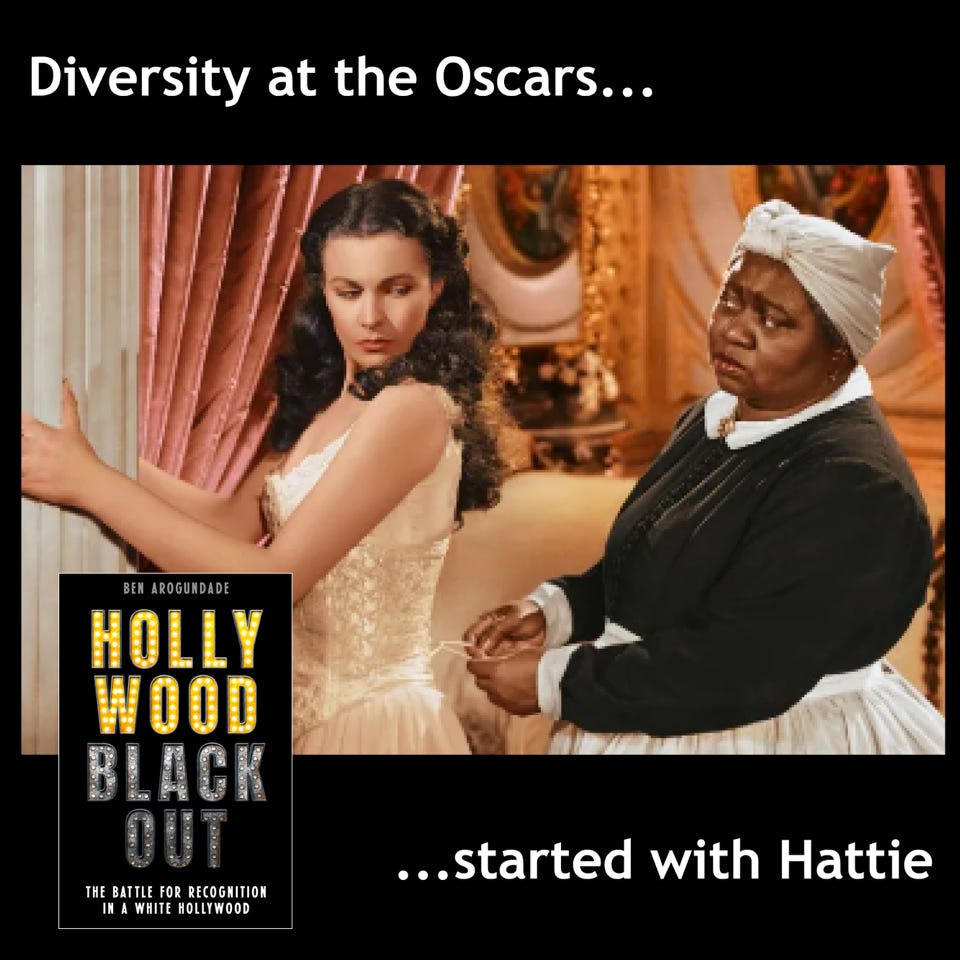

CLASSIC HOLLYWOOD 1940s STYLE: Actresses Vivien Leigh and Hattie McDaniel, star in the 1939 film ‘Gone With The Wind’. McDaniel made movie history in becoming the first person of colour, and the first Black woman, to win an Oscar.

IN FEBRUARY 2020, DURING a campaign rally soon after the movie Parasite won the Oscar for Best Picture, Donald Trump took to the stage and said, “How bad were the Academy Awards this year?...The winner is a movie from South Korea, what the hell was that all about? We got enough problems with South Korea with trade and on top of it, they give them the best movie of the year.” The crowd cheered before he went on to say, “Was it good? I don’t know. I’m looking for, like — can we get like Gone With The Wind back, please?”

Trump’s disapproval of diversity at the Oscars was ironic, given that his favoured film from Hollywood’s so-called Golden Age starred African American actor Hattie McDaniel — who was responsible for kickstarting diversity and inclusion in Hollywood. It began with Gone with the Wind, the novel. It was written by white Southern journalist Margaret Mitchell, and published in 1936. Running to 1,000 pages, it chronicled the epic journey of a white Southern family from the beginning of the American Civil War through to Reconstruction. The narrative focused on the struggles of a young Scarlett O’Hara — a spoilt, petulant Southern belle and daughter to a well-to-do Georgia plantation owner. A cantankerous house slave called Ruth (referred to as Mammy) works at the plantation where she, aside from her domestic duties, doubles as a confidante to Scarlett.

GONE WITH THE WIND SELLS

The book became an instant sensation, selling a million copies in its first six months of sale. It won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1937, and would go on to sell 25 million copies in over 155 editions and translations worldwide. The film rights were purchased by producer David O Selznick for $50,000. But as soon as word got out there were protests from the African American press and civil rights groups. They objected to the book’s sympathetic portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan, and its demeaning portrait of African Americans, including the depiction of slaves as complicit in their own subjugation, and its liberal use of the “N” word to describe them. There were calls for the proposed movie to be scrapped, on the grounds that it would incite greater racial hatred, but the production went ahead regardless.

When Selznick began casting for the role of Mammy, a plethora of candidates came forward to audition. Amongst them was a white actress who proposed to play the role in blackface. Well-to-do whites also attended with their own Black servants in tow, demanding they be screen-tested. The First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, put forward her own servant, White House cook Elizabeth McDuffie, despite the fact that she had no acting experience. In January 1937, Bing Crosby — who was a good friend of McDaniel’s brother Sam — first suggested that Selznick cast her. She coveted the part but suspected she would lose out, as her movie portfolio was mostly comedy. Nevertheless, she screen-tested together with Vivien Leigh playing Scarlett. McDaniel arrived in character, dressed as a typical Southern mammy, which delighted Selznick. The pair enacted the famous bedroom scene at the beginning of the movie, where Mammy laces up Scarlett’s corset from behind. The chemistry between the pair was strong, and by the end of the session Selznick had decided — he’d found his Mammy.

HATTIE MCDANIEL, classic black actress of Hollywood’s so-called Golden era of the 1940s, poses with her Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress, as Mammy in Gone With The Wind.

FAMOUS BLACK ACTRESS SOON TO BE

When Selznick began casting for the role of Mammy, a plethora of candidates came forward to audition. Amongst them was a white actress who proposed to play the role in blackface. Well-to-do whites also attended with their own Black servants in tow, demanding they be screen-tested. The First Lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, put forward her own servant, White House cook Elizabeth McDuffie, despite the fact that she had no acting experience. In January 1937, Bing Crosby — who was a good friend of McDaniel’s brother Sam — first suggested that Selznick cast her. She coveted the part but suspected she would lose out, as her movie portfolio was mostly comedy. Nevertheless, she screen-tested together with Vivien Leigh playing Scarlett. McDaniel arrived in character, dressed as a typical Southern mammy, which delighted Selznick. The pair enacted the famous bedroom scene at the beginning of the movie, where Mammy laces up Scarlett’s corset from behind. The chemistry between the pair was strong, and by the end of the session Selznick had decided — he’d found his Mammy.

In accepting the part, McDaniel decided to try and make it the best it could be, given its racially problematic nature. Taking the role mattered more to her than the pressure from the Black leaders to reject it. They were powerful figures within the community, and growing in influence outside it, but McDaniel defied them. ‘I have never apologized for the roles I played,’ she told The Hollywood Reporter in 1947. She was accused of being more attached to white Hollywood than she was to her own community — and professionally this was true. The Black press and civil rights leaders could not get her work, or national recognition, or Oscars success. Only white movie executives could do that. The film presented a rare opportunity for her to star in a major production alongside some of the biggest names in the business. Clark Gable was cast as Rhett Butler (he and McDaniel had been friends since 1935 when they worked together on the film China Seas). Vivien Leigh was cast as Scarlett O’ Hara, Olivia de Havilland as Melanie Wilkes and Leslie Howard as Ashley Wilkes. It was all systems go.

HATTIE MCDANIEL’S BIOGRAPHY

She was born on 10 June 1893, in Wichita, Kansas. Her parents were former slaves. Her father Henry was a farm labourer, and her mother Susan a domestic servant. The youngest of 13 children, six of her siblings died young. Hattie was malnourished at birth, weighing just three-and-a-half pounds. The family lived in extreme poverty, without adequate clothing or regular meals.

McDaniel’s first love was singing. She’d dreamed of being an entertainer since the age of six, and in school she was popular amongst her classmates for her song-and-dance talents. In 1910 she dropped out to focus on a career as an entertainer, and over the proceeding 20 years she performed in touring minstrel shows with her siblings, establishing herself as a skilled dancer, actor and comedienne, as well as a talented blues singer-songwriter. To make ends meet she worked on the side as a housemaid for white middle-class families.

In 1931 she moved to Los Angeles, where she began securing minor film roles. She knew that making a career in Hollywood would not be straightforward. The roles on offer to Black actors were limited, and she was cast according to physical type. She was dark-skinned, fuller-figured and not conventionally beautiful. This could only mean one thing in the so-called Golden Age of 1930s Hollywood — she would be cast as a mammy. Aesthetically, such figures were stereotyped as overweight, ugly, dark-skinned and adorned with a signature white headwrap. Compliant and forever loyal to their owners, they validated slavery and white supremacy. They were loud, simple-minded, cantankerous, sexless, and much loved by whites as compliant, comic figures.

MCDANIEL - MOVIE MAID & MAMMY

McDaniel auditioned whenever the studios requested mammies or maids. She fit the mould so well that she immediately started working, initially as an extra, at $7.50 per-day ($130 today). Despite the nature of the roles, she was happy to be actively employed in the film business. The pay, though infrequent, was far greater than she’d earn being a real maid. ‘I can be a maid for $7-a-week,’ she once said, ‘or I can play a maid for $700-a-week.’ By the mid-1930s she had become the most prolific actress in Hollywood, featuring in an incredible 15 films per year between 1935 and 1937. She quickly became Hollywood’s go-to actress for comedic, servile, but sharp-tongued mammies.

In 1937 she signed with top Hollywood agent and talent scout William Meiklejohn, otherwise known as ‘the star-maker’. He represented Dorothy Parker, Mickey Rooney, Judy Garland, Lucille Ball and Ronald Reagan. This was a major turning point, as she was one of the only Black stars in Hollywood to have a white agent. She hoped he would secure her more money and better roles — ones that might move her closer to an Academy Award nomination. For Gone With The Wind Meiklejohn negotiated a fee of $450 per week ($10,000 today) for a 15-week shoot.

GONE WITH THE WIND BEGINS

The movie began shooting on 26 January 1939. The production was turbulent, with changes of director and cinematographer, plus 16 different screenwriters, including F. Scott Fitzgerald. The cast endured a myriad of problems, with many scenes being re-shot and dialogue changed last minute. Racial inequalities were also present. On shoot days the studio sent individual limousines for its white actors, while its Black principals were picked up in groups. The on-site restrooms were segregated, with signs for ‘Whites only’ and ‘Colored only’. Clark Gable was outraged, and used his power to insist on their removal.

There were racial disputes during filming, too. McDaniel’s co-star, Butterfly McQueen, raised objections to her demeaning character, Prissy. She protested by deliberately fluffing her lines, and also demanding an apology from Vivien Leigh after complaining that the English actress deliberately slapped her too hard during one of their scenes. McDaniel, watching this saga unfold, later took McQueen quietly to one side and told her: ‘You’ll never come back to Hollywood because you complain too much.’ McDaniel was well aware that Black actors had no power to complain. Their careers were founded on compliance. They survived by embracing silence rather than by speaking out. But McDaniel herself was also caught between two stalls. On one side was a racist Hollywood that she perpetually tried to appease, and on the other were the African American leaders who wanted her to fight against it.

HATTIE’S OSCAR-WINNING QUALITY

Slavery and segregation had separated Black from white, and now McDaniel, in accepting the role of Mammy, found herself separated from her own people too. She knew the only way to win them over was to turn in the performance of her life. She imbued the character with her own ideas from her life and from past theatrical roles she’d played. She improvised many of her lines, injecting just the right range of dramatic emotion every time. Her standout scene occurred on the stairs of the Butler household, when Mammy pleaded tearfully with Melanie Wilkes to comfort a grief-stricken Rhett Butler following the sudden death of his daughter Bonnie in a horse-riding accident. Selznick called it the ‘high emotional point of the film’. The tears McDaniel cried in the scene were real, drawn from memories of her poverty-stricken childhood. ‘They are honest-to-goodness tears; no skinned onion comes near me, nor any other inducer,’ she told a reporter from The Denver Post in April 1941. ‘If tears are slow to come I get to thinkin’ of the meals I missed in my early struggles, and believe you me, they come a gushin’.’ The scene was the one place in the movie where McDaniel got to show her skills as an actor, in portraying sadness and despair. It was a rare opportunity for a Black thespian at that time.

Shooting completed on July 1, 1939. It turned out to be the third most expensive movie ever made at that time, costing $3.85 million ($80 million today). After all its difficulties, the studio was convinced it would flop. Nonetheless, McDaniel’s performance stood out as the production’s big surprise. She had elevated the role of Mammy into something that was not written on the page. Rather than playing her as the slow, elderly, lumbering figure depicted in Mitchell’s novel, McDaniel gave her character an astute vigour and energy. She was bossy, loud, feisty and opinionated. Her performance impressed Selznick so much that, in a telegram to his New York publicist Howard Dietz, he called it ‘one of the great supporting performances of all time’.

GONE WITH THE WIND REVIEWED

Press reviews were split along racial lines. The film was received with great enthusiasm by the mainstream media. The New York Times called it ‘the greatest motion mural we have seen and the most ambitious filmmaking venture in Hollywood’s spectacular history’. McDaniel was singled out for praise. The New York Times called her performance ‘Best of all, perhaps, next to Miss Leigh’, while Variety stated that it was McDaniel ‘who contributes the most moving scene in the film’. By contrast, the African American press were scathing. The Pittsburgh Courier slammed McDaniel and her fellow Black performers for playing ‘happy house servants’ and ‘unthinking hapless clods’, while The Chicago Defender called the film ‘a weapon of terror against black America’.

Undeterred, in early February of 1940, McDaniel went to Selznick’s office armed with a selection of press clippings praising her performance – with some calling for her to be nominated for an Academy Award. She eagerly showed them to Selznick, and urged him to enter her in the Best Supporting Actress category. Pressure had already been mounting for this to happen from within the mainstream press. Two months earlier Edwin Schallert, writing in the Los Angeles Times, had described McDaniel’s performance in the movie as ‘a remarkable achievement’ that was ‘worthy of Academy Supporting awards’. Simultaneously, African American film fans, egged on by local journalists, had written to Selznick demanding that she be put forward. But there was a problem. No African American had ever been nominated before. The Academy Awards were not conceived for their inclusion, and under the rules of segregation they were barred from the venues where they were presented. McDaniel was asking for her civil rights at a time when the movement was still in its infancy. What was she thinking? Did she really think she could get nominated, challenge the supremacy of the white actresses in her category, and possibly even win?

HATTIE MCDANIEL NOMINATED FOR OSCAR

What Selznick did next would turn out to be a pivotal moment in the racial transformation of Hollywood, and perhaps the most important moment ever for Black actors. Glancing at the newspaper cuttings laid before him, he agreed to McDaniel’s request, and the 44-year-old was submitted for the Oscars.

Overall, Gone with the Wind was nominated for an unprecedented 13 Awards, including Clark Gable for Best Actor, Vivien Leigh for Best Actress and Victor Fleming for Best Director. In the Best Supporting Actress category McDaniel was up against some of the finest actors in the world at that time: her Gone with the Wind co-star Olivia de Havilland, Geraldine Fitzgerald (Wuthering Heights), Edna May Oliver (Drums along the Mohawk) and Maria Ouspenskaya (Love Affair).

ON THE EVENING OF 29 FEBRUARY 1940, Tinseltown’s elite gathered for the twelfth annual Academy Awards ceremony at the Cocoanut Grove nightclub at the Ambassador Hotel on Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles. Hattie McDaniel arrived with a beaming smile, and stepped out of her vehicle on the arm of a handsome young escort. They posed for photographers before making their way inside.

Simultaneously, Selznick was hosting a pre-Oscars cocktail party at his home, for some of his nominees and guests. Clark Gable and his wife Carole Lombard were present, as were Vivien Leigh and Laurence Olivier, plus Olivia de Havilland. Then the phone rang. Selznick answered, and listened in silence. On the other end of the line was a journalist from the Los Angeles Times. The paper was about to leak the names of the Academy Award winners in its late edition, and Selznick’s inside man had called to tip him off. As the man spoke, Selznick repeated the names of the winners as his guests waited anxiously. ‘Victor, Hattie. Er, yes. Vivien,’ recalled de Havilland. Her name was not mentioned. Selznick hung up. Her heart sank.

Back at the Ambassador Hotel, as McDaniel entered the venue, unaware of her victory, she became the first African American ever to attend the Oscars. It was one small step for her, and a giant one for the Black diaspora. McDaniel was initially barred from entry to the hotel, which was segregated. Selznick made a special arrangement with the management in order to allow McDaniel and her escort into the building. But her entry was conditional upon her sitting separately. Segregation’s strict rules meant that she could not be seen mingling with her white co-workers, or be captured in press photographs doing so. Instead she was shown to a separate small table at the rear, adjacent to the kitchen – the Hollywood equivalent of being seated ‘at the back of the bus’. There she sat with her escort and Meiklejohn.

HATTIE MCDANIEL’S ACADEMY AWARD

Those seated in the ballroom soon learned that McDaniel had won, as the Los Angeles Times had broken the embargo and published the winners in its 8.45pm edition, much to the Academy’s dismay. When the award was about to be presented, an excited hush descended over the audience. Actress Fay Bainter, who had won the previous year, was compere. In her preamble she hinted at a McDaniel win when she spoke of ‘an America that almost alone in the world today, recognizes and pays tribute to those who give of their best, regardless of creed, race or color’. Her sentiments, though heartfelt, were a pipe dream, as America was still defined by segregation and discrimination. Nevertheless, the big moment had finally arrived. McDaniel’s name was called.

‘Hallelujah!’ she shouted, glancing up to the heavens in gratitude. The 1,200-strong crowd erupted into rapturous applause. She rose proudly to her feet for the walk to the podium that every actor dreams of. In what had been a strong slate of films that year, her competitors had been blessed with better parts and better lines than her in their respective movies – but against all odds, McDaniel, the daughter of slaves, born into extreme poverty, had beaten four of the era’s most talented actresses to one of Hollywood’s most coveted prizes.

HATTIE MCDANIEL’S HISTORIC OSCAR SPEECH

The tone of MeDaniel’s 67-second Oscar speech was humble, grateful and hopeful. She grew tearful as she spoke: ‘I shall always hold it [the Oscar] as a beacon for anything that I may be able to do in the future,’ she said. ‘I sincerely hope I shall always be a credit to my race and to the motion picture industry.’ In her opening remarks, she also made reference to her ‘fellow members of the motion picture industry’. In other words, despite segregation, she saw herself as being very much inside the Hollywood club – an accepted part of the establishment. Nonetheless, while she left the stage as the biggest African American movie star in the world, she still returned to a table segregated by law. But she had moved beyond resentment. In photographs taken in the ballroom, she is looking into the camera, smiling proudly. She was happy – because she’d won. She’d beaten the white actresses. She’d beaten white Hollywood. She had won.

And so had the film. It took a record eight Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay and Best Actress for Vivien Leigh. It went on to become a runaway success, selling 60 million tickets in the first four years of its US release — the equivalent of almost half the population. It would go on to take $393 million at the box office. With adjustment for inflation globally, the Guinness World Records puts the film’s total revenues at $3.44 billion, making it the highest grossing movie of all time, topping more recent blockbusters such as Titanic and Avatar.

The next morning, newspapers across the country carried the sensational story of McDaniel’s historic win, including a number of African American titles that had previously been critical of her role as Mammy, contending that it did nothing to uplift Black people. But ironically, it was this very role that led to her Oscar, which did uplift Black people. If she had listened to them, and turned the role down, she would not have won the Oscar they were now so proud of. McDaniel was well aware of how fickle the whole business was. ‘I’ve learned by livin’ and watchin’ that there is only eighteen inches between a pat on the back and a kick in the seat of the pants,’ she said in a 1941 interview with The Denver Post.

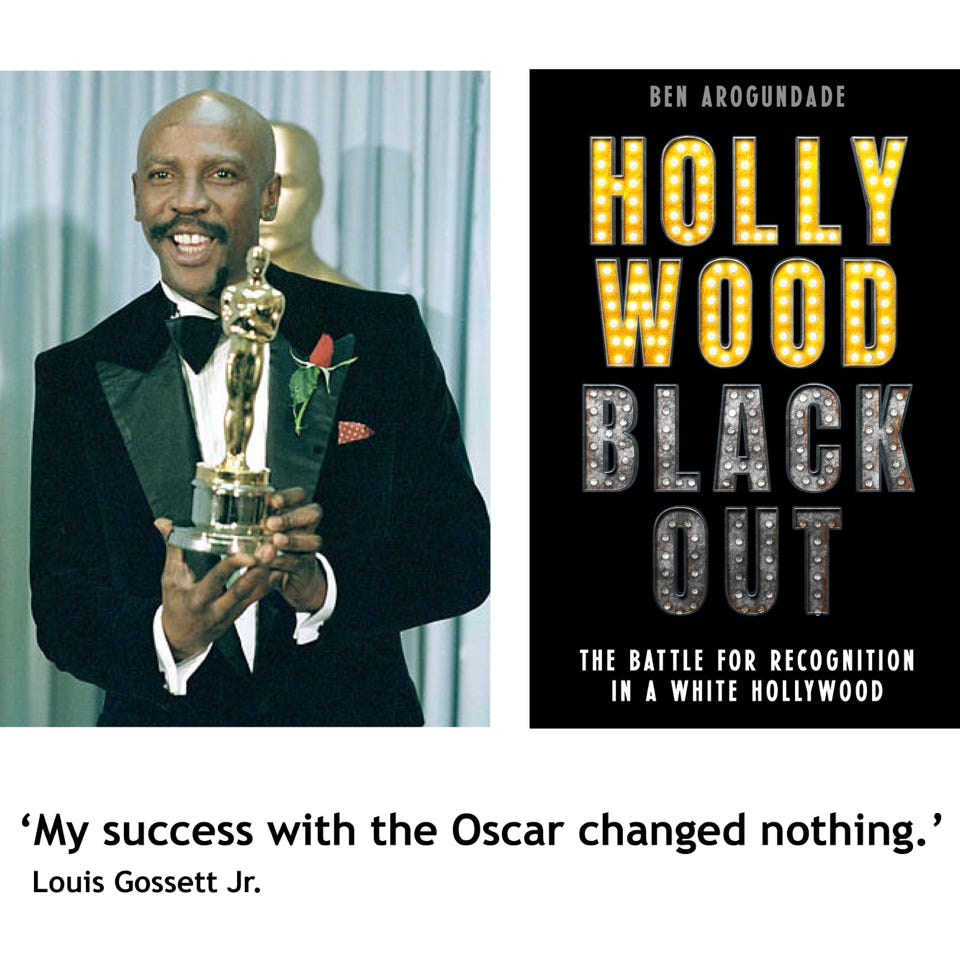

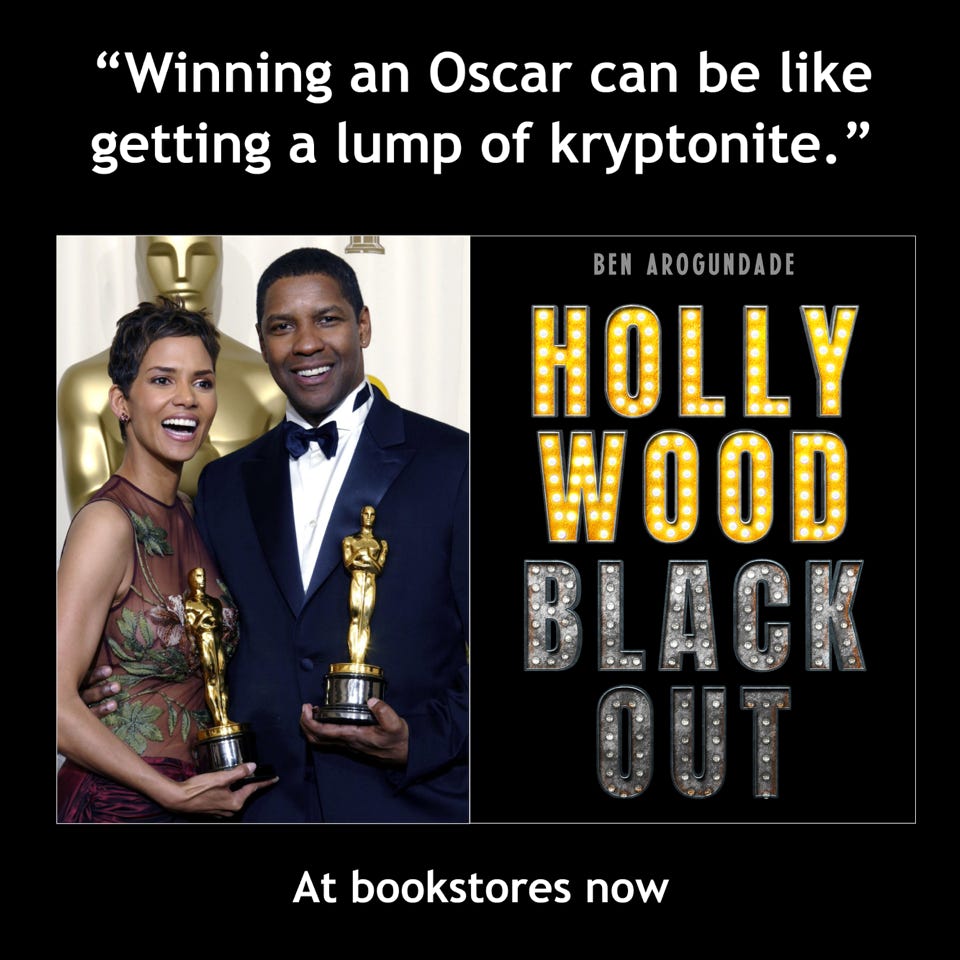

McDaniel’s victory was the first strike of the chisel that began to crack the edifice of the Academy’s resistance to diversity, and to prise open the door for the future nominations and victories of diverse actors of colour and gender, and their attendance as equals on Awards night. But ultimately, Oscars success did not mean more film success for McDaniel. In the aftermath of her victory, her salary did not increase, neither was there was a pile of progressive scripts awaiting her, as was customary for white Oscar winners. Securing an Academy Award would turn out to be easier than getting Hollywood to recognize her as more than just a maid. McDaniel continued to be typecast, playing this role an incredible 74 times in a 17-year career. To Selznick and the other white Hollywood bosses, McDaniel was a mammy – and that was all she could ever be.

The truth was that a Black actress working at that restrictive time in history was never going to secure the roles she yearned for. In fact, in 1947 McDaniel confessed to not having had any film work for two years. Olivia de Havilland, by contrast, would fare better. Although inconsolable after losing out to McDaniel on Oscar night, she needn’t have worried. She would go on to secure a raft of major and diverse roles that would culminate in her winning two Academy Awards for Best Actress. McDaniel, on the other hand, would only get one chance at an Oscar, and after that her career would slide into the dust.

Crucially, McDaniel’s propulsion into the annals of Hollywood history did not happen in a vacuum. She was assisted by political events in the outside world. While her Oscar was held up as a symbol of the Academy’s progressiveness and adherence to liberal, democratic values and fairness, in reality it was the badness of Adolf Hitler that was the catalyst for the goodness of white America in its revisionary treatment of Black people, and in recognizing and rewarding McDaniel’s talent on Oscar night. The rise of Aryan supremacy forced white America to look inwardly and confront its own bigotry. How could they oppose Hitler under the fluttering banners of freedom and liberation, when they were denying these same values to African Americans in their own backyard? How could they talk of going to war against the Nazis, when they were already at war against their own Black citizens? Events in Europe acted like a mirror. A racist America seemed to have to witness somebody else’s badness in order to recognize and confront its own.

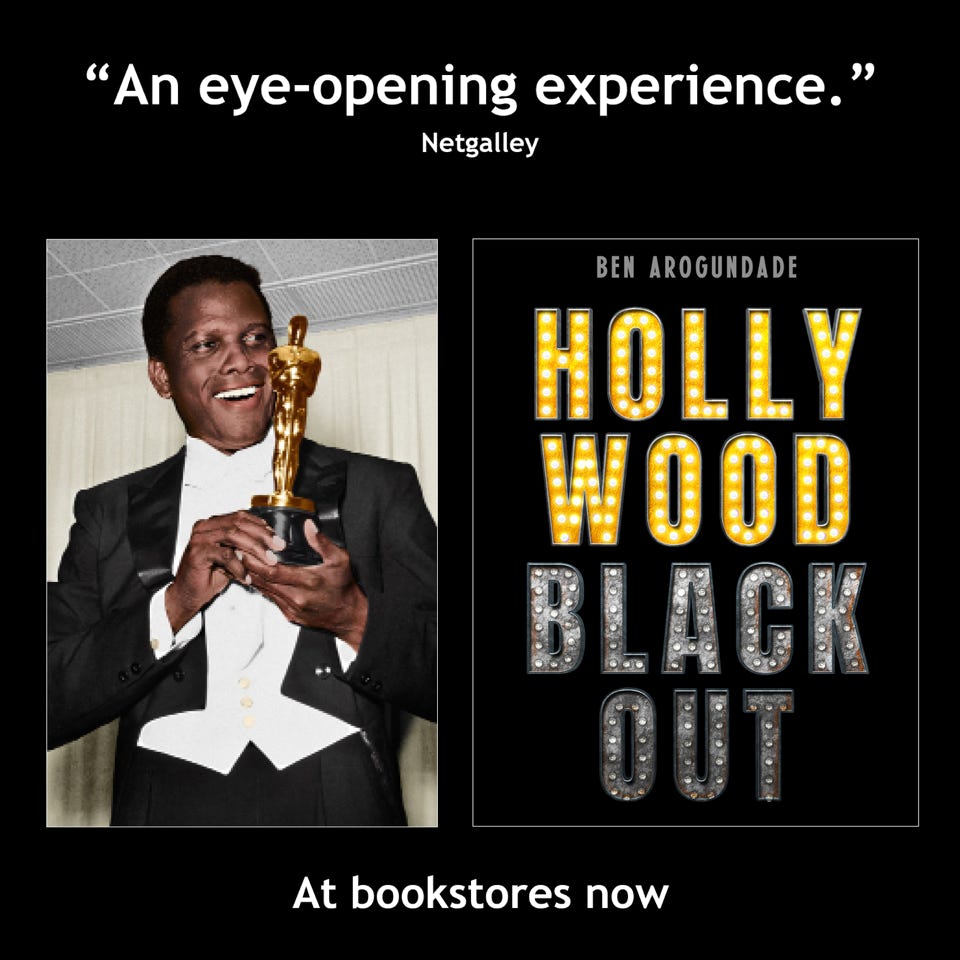

In the decades that followed McDaniel’s Oscar, progress for diversity and inclusion slowed.

Her win did not pave the way for more nominations and wins for actors of colour, as many had hoped and assumed. In fact there were no nominations for Black actors in the two decades afterwards. The Awards remained a private club for white actors, directors, writers and technical staff. The next African American Oscar-winner did not emerge until 1964, when Sidney Poitier won Best Actor for Lilies of the Field. By the end of the 20th century, black actors would only win a total of six times.

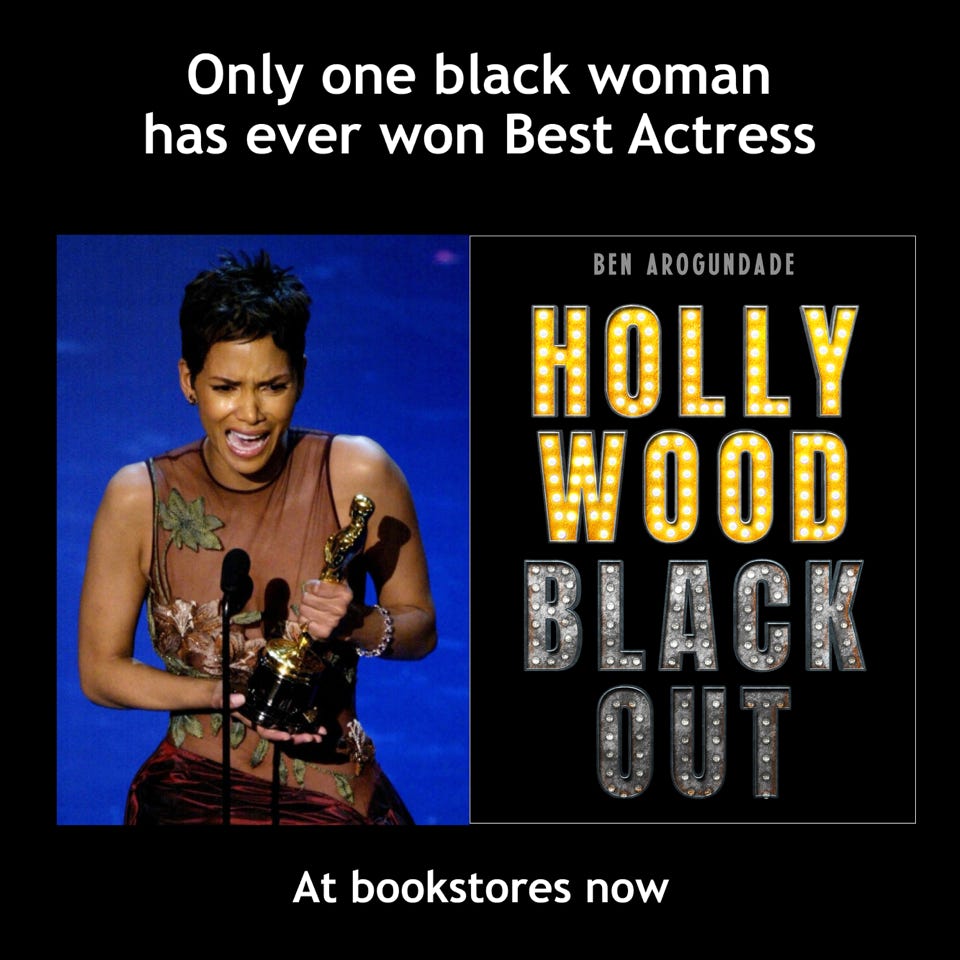

Major issues remain to this day. Only one black woman (Halle Berry for Monster’s Ball), has won Best Actress in almost a century. Black woman have only been successful in winning in Best Supporting roles, where they have done so on ten occasions — and mostly for playing servile roles, similar in style to McDaniel’s. Oscar voters seem to prefer honouring Black women in the guise of servants who are subservient to senior white characters. In 2024 the latest, Da’Vine Joy Randolph, played a fuller-figured cook at a boarding school in The Holdovers — a throwback to McDaniel’s portrayal of Mammy. Hollywood’s power-brokers that are still struggling to visualize Black women as contemporary characters living progressive and complex lives outside the kitchen.

Nevertheless, today’s overall picture is much improved. There have been seventeen black Oscar-winners in the first quarter of this century alone. Now, blacks, Asians, Latinos and LGBTQ+ actors regularly feature in the nominations. The road is much more rainbow-coloured. McDaniel, the woman who started it all, would be amazed if she could witness what has happened to the ceremony since the whites-only segregated affair of her day. Every minority and person of colour who has won an Academy Award since her victory, or who will ever win in the future, owes her a debt, because she was the first one through the door – the ‘atmosphere processor’ – and therefore the one who suffered the most, so that today’s winners would not have to.

Hollywood Blackout, by Ben Arogundade is available at bookstores now.

*HATTIE MCDANIEL - FILMS, OSCARS, BIOGRAPHY - ACCORDING TO GOOGLE SEARCH

250

The number of people worldwide who Google the phrase, “the black maid in Gone With The Wind” each month.

500

The number of people worldwide who Google the phrase, “Hattie McDaniel Oscar speech” each month.

*All figures for “Hattie McDaniel - Films, Oscars, Biography - According to Google Search”, supplied by Google. Stats include global totals for laptop and desktop computers and mobile devices.

ABOUT ME

I am a London-based author, publisher and broadcaster. Discover more about me and my work at Ben Arogundade bio.

© Arogundade, London Town 2025: Registered Office: 85 Great Portland Street, First Floor, London W1W 7LT