The creativity of author, designer, broadcaster Ben Arogundade

What Blade Runner Got Wrong About Architecture

THE ARCHITECTURE WITHIN Ridley Scott’s 1982 sci-fi classic, ‘Blade Runner’, portrayed a future Los Angeles dominated by gigantic buildings and sloping megastructures. But the urban reality of LA in 2019 — when the movie is set — is dramatically different. By Ben Arogundade. December. 13, 2025.

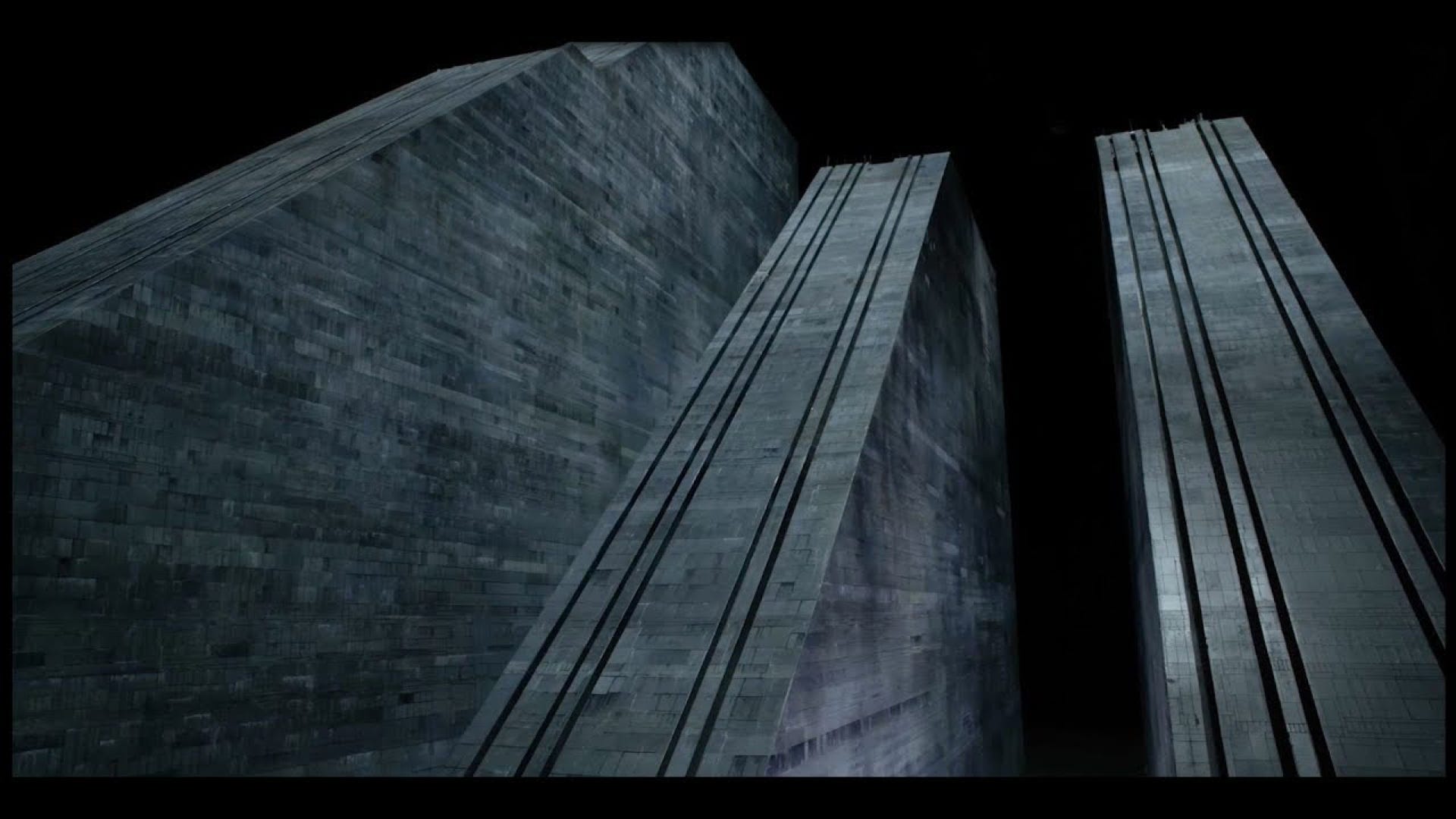

ARCHITECTURE & FILM: Blade Runner’s sloping, pyramid-style buildings are dramatic and imposing, but bear no resemblance to Los Angeles in 2019, when the film is set.

FILM DIRECTOR RIDLEY SCOTT’S 1982 sci-fi classic, Blade Runner, was set in Los Angeles in the year 2019. It offered a dystopian vision of advanced and sometimes malevolent technology, including fully functioning bio-engineered robots cast in human form, called “replicants.” Now that 2019 has come and gone, it’s easy to point out the obvious misses: no flying cars filling the skies, no off-world colonies as an everyday escape valve. But the film’s most revealing miscalculation wasn’t mechanical. It was architectural.

Blade Runner expected the future to announce itself in the skyline: colossal, block-spanning forms; oppressive height; a city remade into a single dense organism. Real 2019 Los Angeles — while changed in meaningful ways — never became that kind of megastructural metropolis. The future, at least in LA, didn’t arrive as a unified new city. It arrived unevenly, in pockets and layers, with the underlying shape of the place staying surprisingly familiar.

THE FILM’S CITY OF BORROWED IDEAS

Part of Blade Runner’s enduring power comes from how convincingly it builds its world. The film doesn’t present “the future” as a clean break. Instead it assembles it from many architectural pasts — like a collage with sharp edges left visible.

Its visual DNA draws from Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and its monumental, hierarchical vertical city; from high-tech architecture such as Richard Rogers’ Pompidou Centre, with its emphasis on exposed systems and industrial aesthetics; from Archigram’s Peter Cook and the dream of plug-in megastructures; from modern corporate icons like the World Trade Center towers; even from the pyramids of ancient Egypt, recast as heavy, symbolic monuments of power.

This mix matters because it reveals what the film thinks architecture is — not just shelter, but ideology made concrete. The city’s forms are temples to corporate dominance, machines for organising life, and instruments for shrinking the human scale. In Blade Runner, buildings don’t merely frame the action. They tell you who controls the world before a character speaks.

THE WRONG PREDICTION: MEGASTRUCTURES AS THE DEFAULT

The clearest thing Blade Runner got wrong about architecture is how comprehensively it expected Los Angeles to transform. The film’s 2019 implies that ordinary urban growth leads almost inevitably to gigantism: overcrowding and land shortages produce extreme verticality, and the result is a skyline of imposing monoliths sprawling across multiple city blocks.

But real Los Angeles in 2019 did not become a continuous field of pyramid-like superstructures. With very few exceptions, much of the city’s everyday architecture still looked a lot like it did decades earlier. Middle-class suburbs remained dominated by low-rise, detached houses rather than sloping-edged megabuildings. Many neighbourhoods retained the same basic rhythm of streets, lots, and small-scale structures — incremental additions rather than total replacement.

Even where LA did build upward, it tended to do so selectively. Growth concentrated in specific districts, along certain corridors, and in particular building types — more “patchwork” than “master plan.” The city never adopted the film’s implied solution of compressing the metropolis into a unified vertical machine.

That mismatch isn’t just a matter of imagination. It reflects how cities actually change. Architecture is shaped less by futuristic possibility than by policy, economics, infrastructure, and local resistance. A film can jump straight to the end state; a real city has to negotiate its way there, lot by lot, permit by permit.

WHY LA STAYED FAMILIAR

Blade Runner treats towering, consolidated density as a natural response to modern pressures. In many places, that’s a credible trajectory. But Los Angeles has long been shaped by forces that pull in different directions.

LA’s built environment has historically been structured around auto-mobility and expansion — roads, parking, distributed commercial strips, and vast low-rise residential areas. Zoning patterns and neighbourhood politics have often favoured preserving single-family character, making the kind of across-the-board vertical overhaul seen in Blade Runner far less likely. Add to that the practical realities of development — financing, land assembly, construction costs, and the complexities of building tall in a seismic region — and you get a city where transformation happens, but not everywhere at once and rarely in a single architectural language.

The film imagines a future where the logical response to density is the megastructure. Real LA responded with a mixture: some densification, some redevelopment, some adaptive reuse, and a great deal of continuity.

THE FUTURE THAT ACTUALLY HAPPENED: INCREMENTAL, NOT TOTAL

If you walk through much of Los Angeles in 2019, the most striking thing isn’t how alien it feels. It’s how legible it remains: a city of recognisable types — houses, small apartment blocks, strip malls, office parks — periodically interrupted by bursts of newness.

That newness is real. There are districts with more towers than before, more glass, more mixed-use development, more vertical living. But the scale tends to be limited, and the experience is uneven. The “future” shows up as infill, as redevelopment along transit and major roads, as clusters of newer buildings rather than an all-consuming skyline.

In other words, Blade Runner expected Los Angeles to become a single, dense, architecturally unified vision. Actual LA became something messier: a city where old and new coexist, where investment collects in some places and bypasses others, where the dominant forms persist even as the edges update.

WHERE THE FILM STILL FEELS RIGHT: TEXTURE AND INEQUALITY

But even if Blade Runner got the shape of 2019 wrong, it captured something that architecture often expresses better than words: social hierarchy.

The film’s architectural landscape is famously textured and dense, and a lot of that comes from its use of real historic Los Angeles buildings for key scenes — such as the Yukon Hotel and the Bradbury Building. In the film, these structures appear as rundown anachronisms: remnants of another era, worn and repurposed, surrounded by looming steel-and-glass power.

That juxtaposition is one of the film’s sharpest observations about cities: the future doesn’t erase the past — it builds over it, leans on it, and often leaves it behind. Old buildings become the setting for precarious lives, informal economies, and marginal characters, while newer construction signals capital, security, and access.

This is also where the film’s sense of isolation lands. Blade Runner understands how large buildings can amplify loneliness — how density doesn’t guarantee connection, and how the scale of the built environment can make people feel like temporary occupants rather than citizens. It also understands how architecture can stage inequality: the widening gulf between rich and poor is not just spoken; it’s built into where people live, what they can access, and how their spaces are maintained.

THE FLYING-CAR DETAIL THAT REVEALS THE REAL FANTASY

One of the film’s most memorable architectural implications is that the buildings are so tall and layered that it’s faster to reach upper floors by flying car than by roads and elevators. It’s a perfect image — because it ties infrastructure, class, and architecture together in a single gesture.

But that image also exposes the film’s biggest architectural fantasy: that a city would reorganise itself around extreme verticality as a default condition for everyday life. Real LA never became that stacked, three-dimensional labyrinth. Its movement systems remained grounded — still oriented around streets, vehicles, and distributed destinations rather than the aerial shortcuts implied by megastructures.

The film’s city is built as a machine that demands new forms of movement. Real LA’s architecture largely stayed within the limits of how people already moved.

WHAT BLADE RUNNER MISSED — AND WHAT IT DIAGNOSED

So what did Blade Runner get wrong about architecture? It overestimated how quickly and how completely the built environment would transform. It mistook cinematic futurism — unified, instantly legible — for the way real cities evolve. Los Angeles in 2019 did not become a landscape of pyramidal monoliths spanning blocks. Much of it remained low-rise, familiar, and stubbornly continuous with earlier decades.

But if the film missed the skyline, it still diagnosed the forces that shape it. Blade Runner understood that architecture is never just background: it is a record of power, a map of inequality, and a machine for producing certain kinds of lives. It imagined those pressures made visible in extreme form.

The real 2019 didn’t look like Blade Runner — not everywhere, not even most places. Yet the film’s most durable idea remains intact: that the future of cities is not only a question of technology, but of who gets space, light, safety, and dignity — and who is left to live in the shadows of someone else’s tower.

BLADE RUNNER BUILDINGS: Sci-fi films regularly misjudge the architecture of the future. While technology consistently yields new devices and inventions, the buildings in which we live and work, mostly stay the same.

More About Hollywood Film

© Arogundade, London Town 2026: Registered Office: 85 Great Portland Street, First Floor, London W1W 7LT